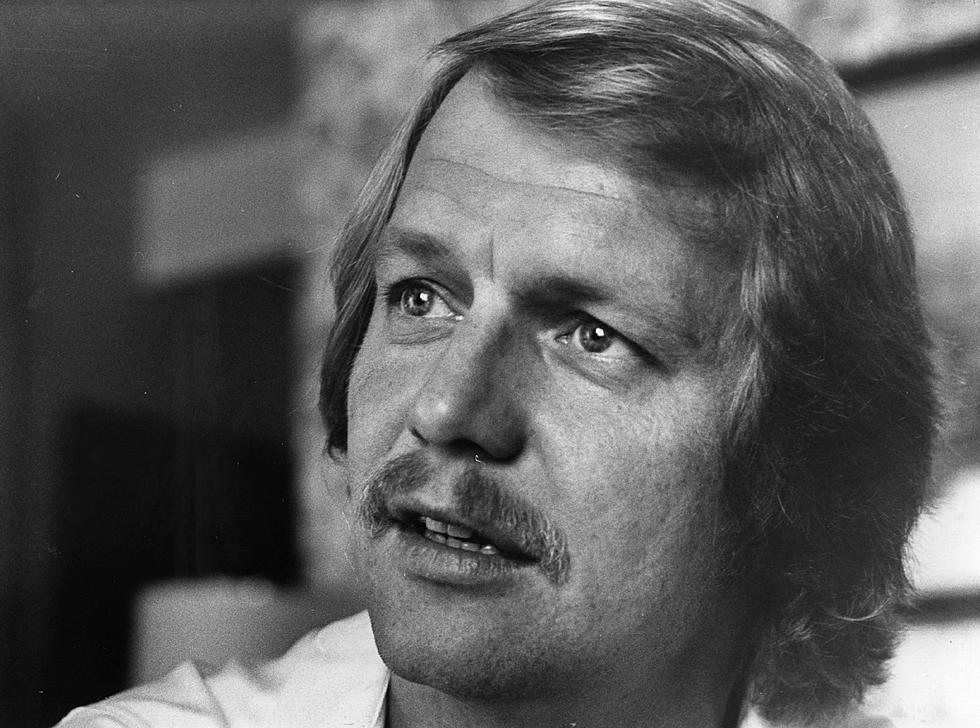

Inventor of Laser Dies

BERKELEY, Calif. (AP) — Charles H. Townes, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who helped create the laser that would revolutionize everything from medicine to manufacturing, has died. He was 99.

Townes had been in poor health before his death on the way to an Oakland hospital Tuesday, officials at the University of California, Berkeley, said.

"Charlie Townes had an enormous impact on physics and society in general," Steven Boggs, the chairman of the physics department at Berkeley, said Wednesday.

The invention he's known for paved the way for other scientific discoveries, but also has a huge array of applications today: DVD players, gun sights, printers, computer networks, metal cutters, tattoo removal and vision correction are just some of the tools and technologies that rely on lasers.

"I realized there would be many applications for the laser," Townes told Esquire magazine in 2001, "but it never occurred to me we'd get such power from it."

Townes was also known for his strong spiritual faith. A devoted member of the United Church of Christ, Townes drew praise and skepticism later in his career with a series of speeches and essays investigating the similarities between science and religion.

"Science tries to understand what our universe is like and how it works, including us humans," Townes wrote in 2005 upon being awarded the Templeton Prize for his contributions in "affirming life's spiritual dimension."

"My own view is that, while science and religion may seem different, they have many similarities, and should interact and enlighten each other," he wrote.

Townes was a faculty member at Columbia University when he did most of the work that would make him one of three scientists to share the 1964 Nobel Prize in physics for research leading to the creation of the laser. The others were Russian physicists Aleksandr M. Prokhorov and Nicolai G. Basov.

Townes' research, the basis of which he often said came to him like a religious revelation, applied the microwave technique used in wartime radar research to the study of spectroscopy, the dispersion of an object's light into its component colors.

He envisioned that would provide a new window into the structure of atoms and molecules and a new basis for controlling electromagnetic waves. His insights eventually led to the first laser.

Born on July 28, 1915, in Greenville, S.C., to Baptist parents who embraced an open-minded interpretation of theology, Townes found his calling during his sophomore year at Furman University and went on to earn a master's degree from Duke University in physics and a doctorate at the California Institute of Technology.

He married his wife, Frances Hildreth Townes, in 1941, and during World War II designed radar bombing systems for Bell Laboratories.

Three years after he joined the Columbia faculty in 1948, Townes had his inspiration for the laser's predecessor, the maser, while sitting on a park bench in Washington, waiting for a restaurant to open for breakfast.

Scientists were stumped about ways to make waves shorter, but in the tranquil morning hours the solution suddenly appeared to Townes, a moment he famously compared to a religious revelation.

Townes scribbled a theory on scrap paper about using microwave energy to stoke molecules to move fast enough to create a shorter wave.

In 1954, that theory was realized when Townes and his students developed the maser (microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation).

Demonstrating that masers could be made to operate in optical and infrared capacities, Townes and his brother-in-law, the late Stanford professor Arthur L. Schawlow, jointly published a theory in 1958 on the feasibility of optical and infrared masers, or lasers.

More From KROC-AM